Understanding Ecological Energy Transfer

In the study of ecology, understanding how energy moves through an ecosystem is fundamental to comprehending how life on Earth is sustained. Two of the most important concepts in this area are food chains and food webs. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably in casual conversation, they represent distinctly different models of energy transfer in nature. Understanding the difference between a food chain and a food web is essential for students, environmental scientists, and anyone interested in how ecosystems function.

Energy in an ecosystem originates primarily from the sun. Through photosynthesis, plants and other producers convert solar energy into chemical energy stored in organic molecules. This energy then passes from one organism to another through feeding relationships. The way we model and visualize these relationships determines whether we are describing a food chain or a food web.

What Is a Food Chain?

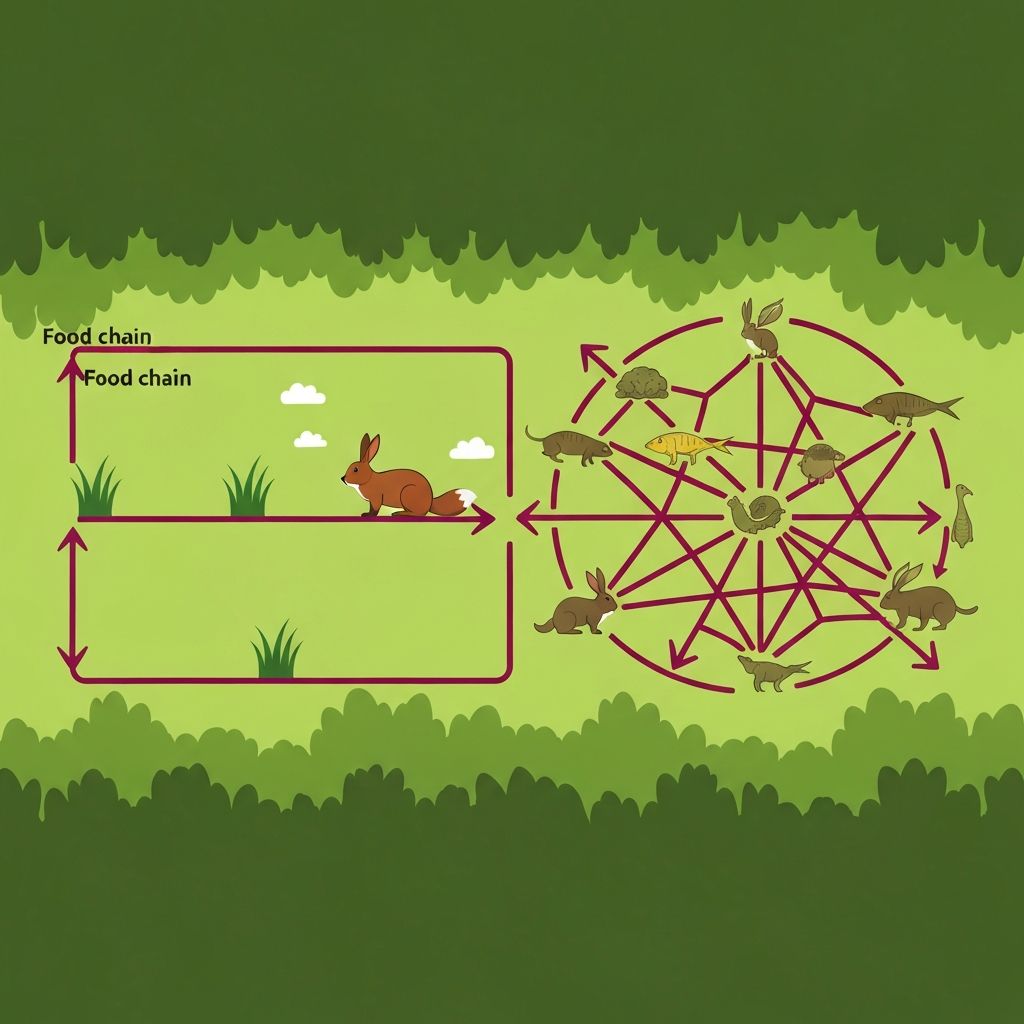

A food chain is the simplest representation of energy flow in an ecosystem. It shows a single, linear pathway through which energy and nutrients pass from one organism to another. Each organism in a food chain occupies a specific position known as a trophic level, and energy flows in one direction from lower trophic levels to higher ones.

A typical food chain consists of four to five trophic levels. At the base are the producers, usually green plants or algae, which convert sunlight into food through photosynthesis. The next level consists of primary consumers, also known as herbivores, which feed directly on producers. Secondary consumers are predators that feed on herbivores, while tertiary consumers are top predators that feed on other predators.

For example, a simple grassland food chain might look like this: grass is eaten by a grasshopper, the grasshopper is eaten by a frog, the frog is eaten by a snake, and the snake is eaten by a hawk. Each arrow in this chain represents the transfer of energy from one organism to the next. At each trophic level, approximately 90% of the energy is lost as heat through metabolic processes, which is why food chains rarely exceed five levels.

Decomposers, such as bacteria and fungi, play a crucial role at every level of the food chain by breaking down dead organic matter and returning nutrients to the soil, where they can be used by producers to start the cycle again.

What Is a Food Web?

A food web is a more complex and realistic representation of the feeding relationships within an ecosystem. Rather than showing a single linear pathway, a food web illustrates the multiple interconnected food chains that exist within an ecosystem. It reveals the intricate network of who eats whom and demonstrates how organisms are linked to one another through multiple feeding relationships.

In a food web, a single organism may occupy different trophic levels simultaneously. For instance, a bear might eat berries as a primary consumer, catch fish as a secondary consumer, and scavenge on the remains of other predators' kills. This versatility in feeding behavior is what makes food webs so much more complex than simple food chains.

Food webs show that most organisms have multiple food sources and are, in turn, consumed by multiple predators. A rabbit, for example, might eat various types of grass, clover, and vegetables, while being preyed upon by foxes, hawks, owls, and snakes. These overlapping relationships create a web-like structure that more accurately reflects the complexity of natural ecosystems.

Key Differences Between Food Chains and Food Webs

The most fundamental difference between a food chain and a food web lies in their complexity. A food chain is linear and straightforward, showing a single path of energy transfer. A food web, on the other hand, is a complex network of multiple food chains interconnected within an ecosystem. Think of a food chain as a single thread, while a food web is the entire tapestry woven from many threads.

In terms of stability, food webs represent more stable ecosystems than food chains. In a simple food chain, if one organism is removed, the entire chain collapses. If the grasshoppers in our earlier example were eliminated, the frogs would lose their food source, which would in turn affect the snakes and hawks. In a food web, however, organisms have alternative food sources, so the removal of one species, while impactful, doesn't necessarily cause the entire system to collapse.

Accuracy is another key difference. Food chains are simplified models that are useful for educational purposes and for understanding basic energy flow, but they don't accurately represent the full complexity of nature. Food webs provide a much more realistic picture of how ecosystems actually function, showing the true diversity of feeding relationships that exist in nature.

The scope of each model also differs significantly. A food chain focuses on a specific sequence of organisms, while a food web encompasses all the feeding relationships within an entire ecosystem. Food webs can include dozens or even hundreds of species and thousands of individual feeding interactions.

Trophic Levels in Food Chains vs. Food Webs

In a food chain, each organism occupies a single, clearly defined trophic level. Producers are always at the first level, primary consumers at the second, and so on. This rigid structure makes food chains easy to understand and analyze, but it oversimplifies the reality of most organisms' diets.

In a food web, organisms can occupy multiple trophic levels simultaneously. Omnivores, which eat both plants and animals, are perfect examples of this. A human, for instance, acts as a primary consumer when eating a salad and as a secondary or tertiary consumer when eating a steak or fish. This multi-level positioning is impossible to represent in a simple food chain but is easily accommodated in a food web.

The concept of trophic levels becomes more nuanced in food webs, where scientists often calculate a fractional trophic level for organisms based on the proportion of their diet that comes from different sources. This provides a more accurate understanding of each organism's role in the ecosystem.

Energy Flow and the 10% Rule

Both food chains and food webs are governed by the same fundamental principles of energy transfer. The 10% rule, also known as the law of energy transfer, states that only about 10% of the energy at one trophic level is transferred to the next level. The remaining 90% is lost as heat through cellular respiration and metabolic processes.

This energy loss explains why there are typically fewer organisms at higher trophic levels. It takes a large amount of plant material to support a smaller population of herbivores, which in turn supports an even smaller population of predators. This is known as an ecological pyramid and is visible in both food chains and food webs.

In food webs, the energy transfer becomes more complex because organisms receive energy from multiple sources. A secondary consumer might get energy from several different primary consumers, and the efficiency of energy transfer can vary between different feeding relationships. This complexity makes energy flow calculations in food webs significantly more challenging than in simple food chains.

Real-World Examples

Consider a marine ecosystem. A simple food chain might show: phytoplankton is eaten by zooplankton, zooplankton is eaten by small fish, small fish are eaten by larger fish, and larger fish are eaten by sharks. This chain is accurate but incomplete.

The corresponding food web would show that phytoplankton is consumed not only by zooplankton but also by small fish, jellyfish, and filter-feeding whales. Zooplankton serves as food for small fish, sea birds, and baleen whales. Small fish are consumed by larger fish, seals, dolphins, and sea birds. Each of these organisms may also be connected to other food sources, creating an intricate web of relationships.

In a forest ecosystem, a food chain might follow the path of oak leaves to caterpillars to songbirds to hawks. But the food web would reveal that oak trees also produce acorns eaten by squirrels, deer, and wild turkeys. Caterpillars are eaten not only by songbirds but also by mice and other insects. Songbirds consume a variety of insects, seeds, and berries. Hawks prey on songbirds, mice, snakes, and rabbits. This web of interconnections paints a far more complete picture of the ecosystem.

Importance in Environmental Science

Understanding the difference between food chains and food webs has practical implications for environmental conservation and management. When scientists assess the potential impact of removing or adding a species to an ecosystem, they rely on food web models to predict cascading effects throughout the system.

The concept of keystone species, organisms whose removal would cause disproportionate changes to an ecosystem, can only be properly understood within the context of a food web. For example, the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park triggered a trophic cascade that affected not just the elk they preyed upon, but ultimately changed the flow of rivers by allowing vegetation to regrow along waterways.

Climate change, pollution, and habitat destruction all have the potential to disrupt food webs in complex and sometimes unpredictable ways. By studying food webs, scientists can better predict and mitigate the effects of these environmental challenges, making food web analysis a critical tool in conservation biology.

Conclusion

While food chains and food webs both describe how energy flows through ecosystems, they do so at very different levels of complexity and accuracy. Food chains provide a simple, linear model that is useful for basic understanding, while food webs offer a comprehensive, interconnected view that more accurately represents the complexity of natural ecosystems. Both concepts are essential tools in ecology, and understanding their differences helps us better appreciate the intricate balance of life on Earth and the importance of preserving biodiversity within our ecosystems.