What Is a Food Web and Why Does It Matter

A food web is a visual representation of the complex feeding relationships within an ecosystem. Unlike a simple food chain, which shows a single linear pathway of energy transfer from one organism to another, a food web illustrates the interconnected network of multiple food chains that exist within the same ecosystem. This interconnected view provides a much more accurate and comprehensive picture of how energy and nutrients flow through a biological community.

Understanding food webs is fundamental to the study of ecology because they reveal the dependencies and relationships between different species in an ecosystem. When one species in a food web declines or disappears, the effects ripple throughout the entire network, potentially impacting dozens of other species. This concept, known as a trophic cascade, helps scientists predict and manage the ecological consequences of environmental changes, habitat loss, invasive species introductions, and other disturbances.

Whether you're creating a food web for a school science project, a biology class assignment, or personal interest in ecology, the process follows a systematic approach that begins with identifying the organisms in your chosen ecosystem and ends with a detailed diagram showing all the feeding connections between them.

Step 1: Choose Your Ecosystem

The first step in creating a food web is selecting the ecosystem you want to study. An ecosystem can range from a small, contained environment like a backyard pond or a rotting log to a vast biome like the African savanna or the Pacific Ocean. For beginners and school projects, it's often best to start with a well-documented ecosystem where information about the resident species and their diets is readily available.

Popular ecosystems for food web projects include temperate forests, grasslands, coral reefs, freshwater ponds, arctic tundra, and desert environments. Each of these ecosystems has a well-established body of scientific literature describing the organisms that live there and their feeding relationships. Choose an ecosystem that interests you, as your enthusiasm will show in the quality and detail of your finished food web.

Once you've selected your ecosystem, take time to research it thoroughly. Learn about its climate, geography, seasonal patterns, and the types of habitats it provides. This background knowledge will help you identify the key organisms and understand why certain feeding relationships exist within the system.

Step 2: Identify the Organisms

With your ecosystem selected, the next step is to identify the organisms that will be included in your food web. Start by categorizing organisms into their trophic levels, which represent their position in the food chain hierarchy. The primary trophic levels are producers, primary consumers, secondary consumers, tertiary consumers, and decomposers.

Producers are organisms that create their own food through photosynthesis or chemosynthesis. In most ecosystems, these are plants, algae, and certain bacteria. They form the base of the food web and are essential because they convert solar energy into chemical energy that other organisms can use. List all the significant producers in your chosen ecosystem, such as grasses, trees, shrubs, phytoplankton, or mosses.

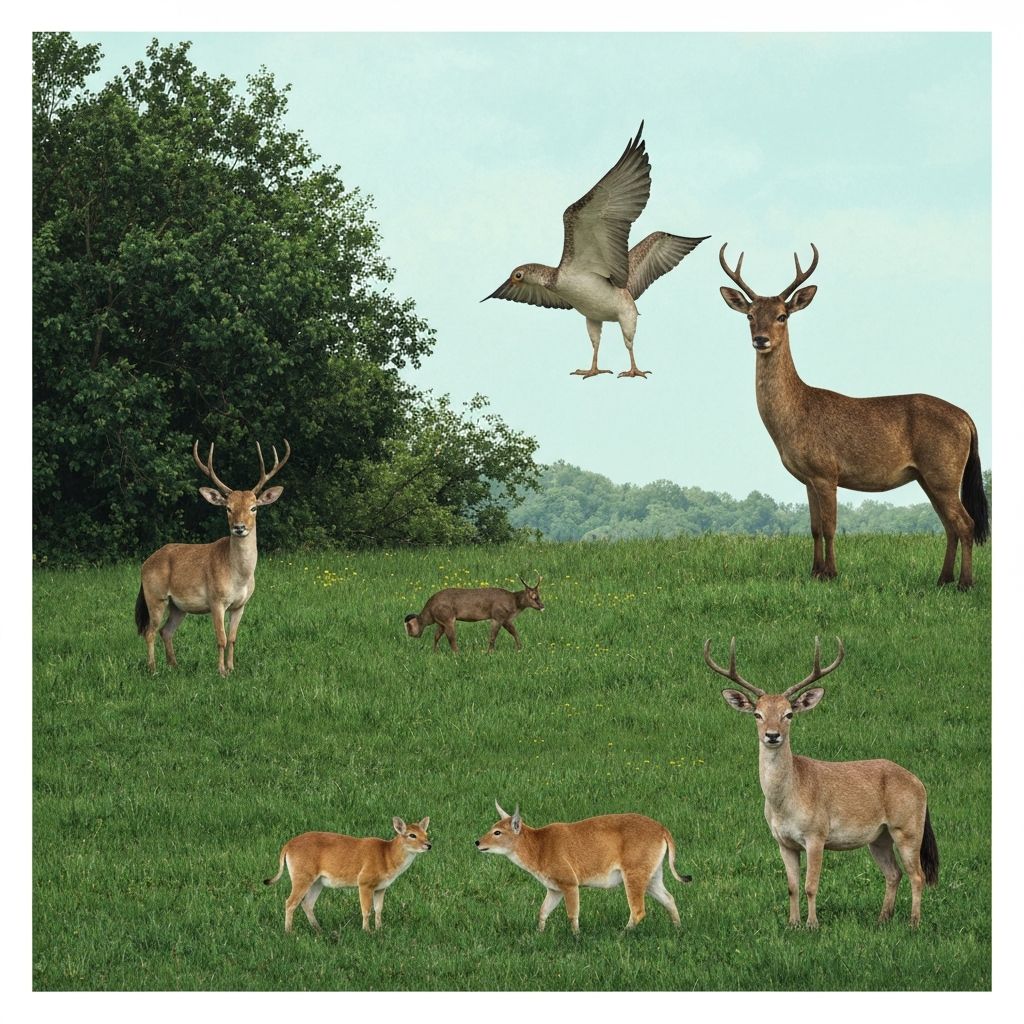

Primary consumers are herbivores that eat producers. These include animals like rabbits, deer, caterpillars, zooplankton, and grasshoppers. Secondary consumers are carnivores or omnivores that eat primary consumers, such as frogs, small birds, foxes, and predatory insects. Tertiary consumers, also called apex predators, sit at the top of the food web and eat secondary consumers. Examples include eagles, sharks, wolves, and large cats. Finally, decomposers like bacteria, fungi, and certain insects break down dead organisms from all trophic levels and return nutrients to the soil.

Step 3: Research Feeding Relationships

Once you've identified the organisms in your food web, research the specific feeding relationships between them. For each consumer in your web, determine what it eats and what eats it. This information forms the connections, or links, in your food web diagram.

Use reliable sources for your research, including ecology textbooks, peer-reviewed scientific papers, reputable wildlife databases, and educational resources from universities and natural history museums. Be as specific as possible in documenting feeding relationships. Rather than simply noting that a bird eats insects, identify which specific bird species eat which specific insect species in your chosen ecosystem.

Keep in mind that many organisms are omnivores that eat from multiple trophic levels, and many prey species are consumed by multiple predators. These overlapping relationships are what distinguish a food web from a simple food chain and make the diagram more complex and realistic. Document all the relationships you discover, as each one represents an important energy pathway in the ecosystem.

Step 4: Organize Your Information

Before you start drawing your food web, organize all the information you've gathered into a clear and structured format. Create a table or list that shows each organism, its trophic level, what it eats, and what eats it. This reference document will serve as your blueprint when constructing the visual diagram.

Group organisms by trophic level, with producers at the bottom, followed by primary consumers, secondary consumers, and tertiary consumers at the top. Decomposers can be placed to the side of the main diagram, as they interact with organisms at all trophic levels. This hierarchical arrangement is the standard convention for food web diagrams and makes the flow of energy easy to follow.

Decide how many organisms to include in your food web. A comprehensive food web for even a simple ecosystem can include dozens of species and hundreds of connections, which can quickly become overwhelming. For most purposes, selecting 15 to 25 representative organisms that illustrate the key feeding relationships in the ecosystem provides a good balance between accuracy and readability.

Step 5: Draw Your Food Web

Now it's time to create the visual diagram. You can draw your food web by hand, use a computer drawing program, or utilize specialized food web software. Regardless of the method, the basic approach is the same. Place the producers at the bottom of the diagram, arrange consumers in ascending trophic levels above them, and draw arrows from each food source to the organism that eats it. The arrows represent the direction of energy flow, always pointing from the prey to the predator.

Use clear, labeled images or symbols to represent each organism. Color-coding organisms by trophic level can help make the diagram easier to read: green for producers, blue for primary consumers, orange for secondary consumers, and red for tertiary consumers. Use a consistent arrow style throughout the diagram and try to minimize crossing lines where possible to maintain visual clarity.

Include a title for your food web that specifies the ecosystem it represents. Add a legend explaining any symbols, colors, or abbreviations you've used. If your food web is for an academic assignment, include labels for each trophic level and a brief description of the ecosystem at the bottom or side of the diagram.

Step 6: Analyze and Refine

After completing your initial diagram, review it carefully for accuracy and completeness. Verify that all feeding relationships are correctly represented and that arrows point in the right direction. Check that you haven't omitted any significant organisms or connections that would affect the overall picture of energy flow in the ecosystem.

Consider adding annotations that highlight interesting ecological concepts illustrated by your food web. For example, you might identify keystone species whose removal would cause significant disruption to the food web, or highlight examples of competitive relationships where multiple predators share the same prey. These annotations demonstrate a deeper understanding of ecological principles and add educational value to your food web.

Finally, think about what your food web reveals about the health and resilience of the ecosystem. A food web with many interconnections is generally more resilient than one with few connections, because the loss of any single species can be partially compensated by alternative energy pathways. Conversely, a food web with few connections or where many species depend on a single food source is more vulnerable to disruption.