Is Copper Really a Magnetic Material?

The statement "copper is a magnetic material" is a common misconception that deserves careful examination. In everyday experience, copper does not behave like the magnetic materials we're familiar with — it doesn't stick to refrigerator magnets, it can't be picked up by a magnet, and it doesn't retain magnetic properties the way iron, nickel, or cobalt do. However, copper does interact with magnetic fields in fascinating and scientifically important ways, which may be the source of this widespread confusion.

To understand copper's relationship with magnetism, we need to explore the different types of magnetic behavior that materials can exhibit. Materials are classified into several magnetic categories based on how their atomic structure responds to external magnetic fields: ferromagnetic, paramagnetic, diamagnetic, and antiferromagnetic. Each category describes a fundamentally different interaction with magnetic fields, and understanding these categories is key to understanding why copper behaves the way it does.

Copper is classified as a diamagnetic material, which means it is very weakly repelled by magnetic fields rather than attracted to them. This diamagnetic effect is extremely subtle — so subtle that it's imperceptible without sensitive laboratory equipment. In practical terms, copper is considered non-magnetic because its interaction with magnetic fields is too weak to produce any noticeable effect in everyday situations.

Understanding Diamagnetism in Copper

Diamagnetism is a quantum mechanical property that arises from the orbital motion of electrons around atomic nuclei. When an external magnetic field is applied to a diamagnetic material, it induces a small change in the orbital motion of the electrons, creating tiny magnetic moments that oppose the applied field. This opposing effect is what causes the very weak repulsion between diamagnetic materials and magnets.

In copper atoms, the electron configuration (with 29 electrons arranged in specific energy levels and orbitals) does not produce any net magnetic moment in the absence of an external field. The electrons are arranged in pairs that cancel each other's magnetic effects, resulting in a material with no inherent magnetism. When an external magnetic field is applied, the induced diamagnetic response is present but extremely small — copper's magnetic susceptibility is approximately -9.63 times 10 to the negative sixth power, indicating a very weak diamagnetic response.

It's worth noting that all materials exhibit some degree of diamagnetism, but in ferromagnetic and paramagnetic materials, the diamagnetic effect is overwhelmed by much stronger magnetic interactions. In copper and other diamagnetic materials like gold, silver, bismuth, and water, diamagnetism is the dominant magnetic behavior because there are no stronger magnetic effects to overshadow it.

The diamagnetic repulsion of copper has been dramatically demonstrated in laboratory settings using powerful superconducting magnets. Under sufficiently strong magnetic fields, small pieces of diamagnetic materials — including copper — can be levitated, suspended in mid-air by the repulsive force between the material and the magnetic field. While this demonstration is impressive, it requires magnetic field strengths far beyond what normal permanent magnets can produce.

Copper and Electromagnetic Induction

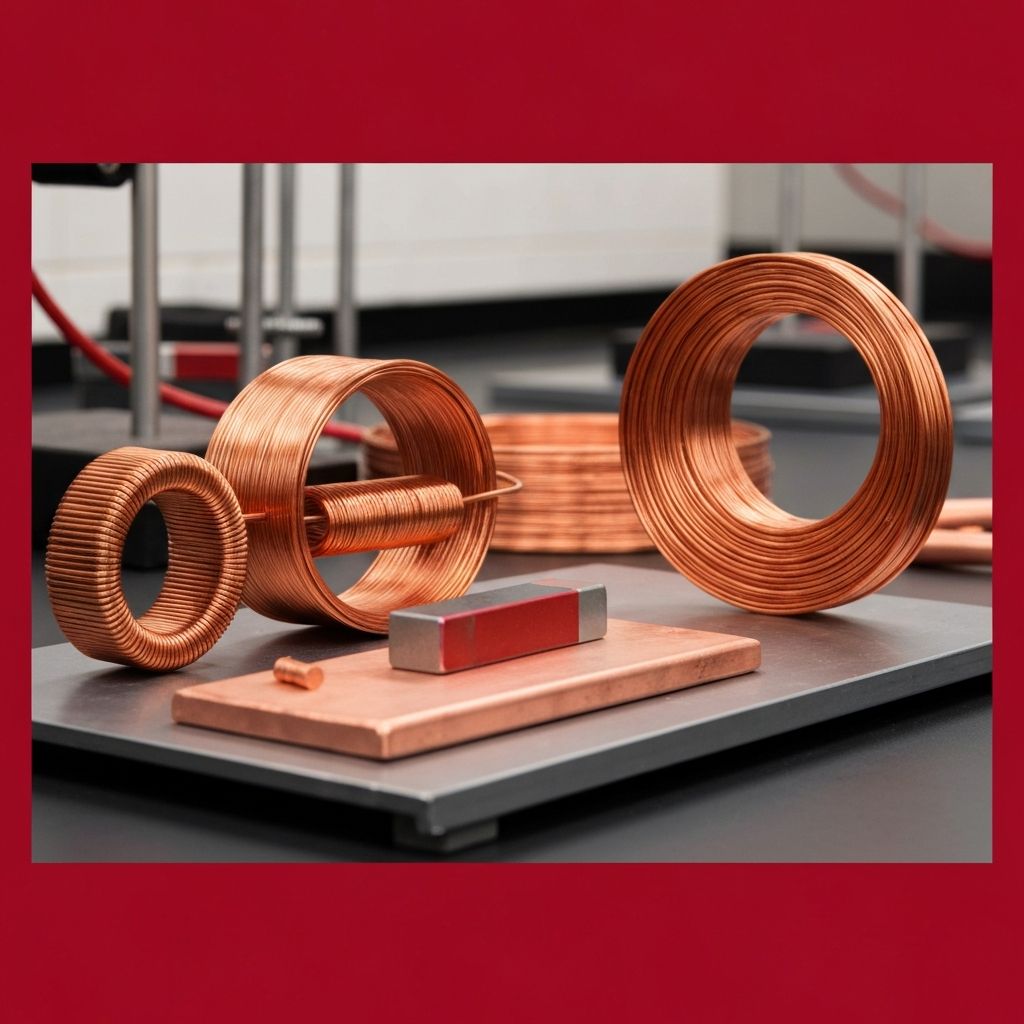

While copper's diamagnetic properties are too weak to be practically significant, copper has an extremely important relationship with magnetism through the phenomenon of electromagnetic induction. When a changing magnetic field passes through a copper conductor, it induces an electric current in the copper. This principle, discovered by Michael Faraday in 1831, is the foundation of modern electrical power generation, electric motors, transformers, and countless other technologies.

The reason copper is so important in electromagnetic applications is its exceptional electrical conductivity — copper is the second most electrically conductive element after silver, and its combination of high conductivity, ductility, and relative affordability makes it the material of choice for electrical wiring, motor windings, transformer coils, and power transmission lines worldwide.

A striking demonstration of copper's interaction with changing magnetic fields is the Lenz's law experiment, where a strong neodymium magnet is dropped through a copper tube. As the magnet falls through the tube, the changing magnetic field induces circular currents (called eddy currents) in the copper walls. These eddy currents create their own magnetic field that opposes the motion of the falling magnet, dramatically slowing its descent. The magnet appears to fall in slow motion through the copper tube, as if passing through a viscous liquid.

This experiment perfectly illustrates why people sometimes believe copper is magnetic — the dramatic interaction between the magnet and the copper tube looks like magnetic attraction or repulsion. In reality, the effect is entirely due to electromagnetic induction and the resulting eddy currents, not any inherent magnetic property of the copper itself. The interaction only occurs with changing magnetic fields; a stationary magnet placed next to a piece of copper will not produce any noticeable effect.

Ferromagnetic vs. Non-Magnetic Materials

To fully appreciate why copper is not magnetic in the conventional sense, it helps to understand what makes ferromagnetic materials — the materials we typically think of as "magnetic" — different from copper and other non-magnetic materials.

Ferromagnetic materials, which include iron, nickel, cobalt, and certain alloys, have a unique atomic structure that allows neighboring atoms to align their magnetic moments in the same direction, creating regions of uniform magnetization called magnetic domains. When an external magnetic field is applied, these domains can grow and align, producing a strong net magnetic field that persists even after the external field is removed. This is why a piece of iron can be permanently magnetized.

Copper's atomic structure does not support this type of magnetic domain formation. Its electrons are arranged in configurations that produce no net magnetic moment, and there is no mechanism for neighboring copper atoms to align their magnetic properties cooperatively. This is why copper cannot be magnetized by exposure to a magnetic field and why it doesn't stick to permanent magnets.

Paramagnetic materials, such as aluminum and platinum, fall between ferromagnetic and diamagnetic materials. They have unpaired electrons that create small magnetic moments, and these moments tend to align with an applied magnetic field, causing a weak attraction. However, unlike ferromagnetic materials, paramagnetic materials cannot retain magnetization after the external field is removed. Copper is not paramagnetic — it lacks the unpaired electrons needed for paramagnetic behavior.

Copper in Electrical and Magnetic Applications

Despite not being magnetic itself, copper plays an indispensable role in virtually every magnetic and electromagnetic application in modern technology. Its high electrical conductivity makes it the ideal material for conducting the electric currents that create, control, and utilize magnetic fields in everything from simple electromagnets to sophisticated particle accelerators.

Electric motors and generators rely on copper windings to create the electromagnetic interactions that convert between electrical and mechanical energy. In a motor, electric current flowing through copper coils creates magnetic fields that interact with permanent magnets or other electromagnets to produce rotation. In a generator, the process is reversed — mechanical rotation moves copper coils through magnetic fields, inducing electric current that is used to power electrical devices.

Transformers use copper coils wound around magnetic cores to transfer electrical energy between circuits at different voltages. The alternating current in the primary copper coil creates a changing magnetic field in the core, which induces a voltage in the secondary copper coil. The ratio of turns in the primary and secondary coils determines the voltage transformation ratio. Copper's low electrical resistance minimizes energy losses in this process, making transformers highly efficient.

Electromagnetic shielding is another important application where copper's electrical properties are leveraged in the context of magnetic fields. Copper enclosures and meshes can block electromagnetic interference (EMI) by absorbing and reflecting electromagnetic waves. The eddy currents induced in the copper by the electromagnetic waves create opposing fields that cancel the incoming waves, protecting sensitive electronics from interference.

Common Misconceptions About Copper and Magnetism

Several common misconceptions about copper and magnetism are worth addressing to provide a clearer understanding of the material's properties. The first and most prevalent misconception is the one stated in our title — that copper is a magnetic material. As we've discussed, copper is diamagnetic, meaning it has an extremely weak repulsive interaction with magnetic fields that is imperceptible in everyday situations.

Another common misconception is that copper can be magnetized. Unlike iron and steel, copper cannot acquire permanent magnetic properties through exposure to a magnetic field. No matter how strong a magnet you place next to a piece of copper, the copper will not become magnetized. This is a fundamental consequence of copper's electron configuration and crystal structure.

Some people confuse copper's excellent electrical conductivity with magnetic properties. While conductivity and magnetism are related through electromagnetic induction, they are distinct physical properties. A material can be an excellent electrical conductor without being magnetic (like copper and silver), and a material can be strongly magnetic without being a good conductor (like certain ceramic ferrite magnets).

The Lenz's law demonstration with a magnet falling through a copper tube also leads to misconceptions. Observers often conclude that the copper must be magnetic because of the dramatic slowing effect on the falling magnet. In reality, this effect is entirely due to electromagnetic induction and the resulting eddy currents — it requires a changing magnetic field and would not occur with a stationary magnet.

Copper Alloys and Magnetic Properties

While pure copper is diamagnetic, some copper alloys can exhibit different magnetic behaviors depending on the alloying elements. This is another area where confusion about copper's magnetic properties can arise, as people may encounter a copper-colored material that responds to a magnet and incorrectly conclude that copper is magnetic.

Copper-nickel alloys (cupronickel), which are widely used in coins and marine applications, can exhibit weak paramagnetic behavior due to the presence of nickel, which is a ferromagnetic element. However, at the nickel concentrations typically used in these alloys (usually 10 to 30 percent), the alloy does not exhibit strong ferromagnetic behavior — it may respond very weakly to a strong magnet but will not stick to it firmly like iron would.

Copper-iron alloys can also exhibit magnetic properties due to the iron content. Certain precipitation-hardened copper alloys that contain iron particles distributed throughout the copper matrix can be noticeably attracted to magnets, especially if the iron content is high enough to form ferromagnetic clusters within the copper. These alloys are used in specialized applications where both copper's conductivity and some magnetic response are desirable.

Manganese-copper alloys are of particular scientific interest because of their complex magnetic behaviors. Certain compositions of these alloys exhibit spin glass behavior — a disordered magnetic state that has been the subject of extensive research in condensed matter physics. These alloys demonstrate that the magnetic properties of copper-based materials can be dramatically altered by the addition of other elements.

The Importance of Accurate Scientific Understanding

Understanding why copper is not magnetic in the conventional sense, while still playing a crucial role in magnetic and electromagnetic technologies, illustrates the importance of precise scientific language and accurate understanding of material properties. The distinction between being magnetic (having inherent magnetic properties) and interacting with magnetic fields (through phenomena like electromagnetic induction) is fundamental to materials science, electrical engineering, and physics.

For students and educators, the copper-magnetism question provides an excellent teaching opportunity. It introduces important concepts such as diamagnetism, electromagnetic induction, Lenz's law, and the classification of magnetic materials — all of which are foundational topics in physics and engineering curricula. Exploring why copper behaves the way it does around magnets leads to a deeper understanding of both magnetism and electricity.

For engineers and technologists, accurate knowledge of copper's magnetic properties is essential for designing effective electrical and electronic systems. Understanding that copper is not magnetic but is an excellent conductor helps in selecting the right materials for specific applications, from power generation and transmission to electronic shielding and sensor design. The interplay between copper's electrical and magnetic behaviors is at the heart of modern technology.